This is the thirteenth installment in the series Get Your Facts Straight: Research Skills for Writers. For more about this 18-part series, including the complete schedule and the Table of Contents with links to all the other articles in the series, click here.

Here’s some news you can use: most research about sex is terrible. Very little of it is particularly meaningful or trustworthy, and yes, that includes some of what has been published in peer-reviewed journals.1

This is nothing new. Most research about sex has always been terrible. This is also true of research about gender, and for every related or connected topic under the sun, literally from cradle (where *do* babies come from?) to grave (people’s fascination with necrophilia, forgive me for saying so, never dies).

I know extremely well how bad the research is because I’ve done a lot of research-based work on sexuality topics: I wrote the first ever history of virginity, I’ve written a history of the concept of heterosexuality, and spent decades of my working life hip-deep in sexuality research of various kinds. There is a lot, and I do mean a lot, of dreck out there.

This is not because people who do research about sexuality are bad people or bad scholars. As in every other field of endeavor there are a few folks who are most relevant as bad examples. But most researchers who work on sex and gender and the whole constellation of related issues do the best they can with what they have to work with. What we have to work with, though, is often sketchy, incomplete, and poor.

Belief, Bias, and Bad Research

The problems with sexuality and gender research have their roots in intense and intensely emotional biases. Sex and gender are profoundly emotional topics for most people, tied up not just in religion and law but in our own experiences of our bodies, our interpersonal relationships, and the basic behavioral rules of our societies. These are central aspects of what makes us human. It would be weird if our emotions weren’t involved.

Sex and gender also get to us on an emotional level because they are, by nature, profoundly anarchic, not just in terms of what people do and how they behave but also, at times, in terms of actual biology and physiology.2 But human beings prefer order to anarchy. Various forms of social order, in fact, are what let us form societies in which we can function and have understandable, reliable relationships with one another.

Sexuality and gender have always presented threats to that order. Human beings have therefore historically navigated the wild and sometimes unpredictable diversity of sexuality and gender by imposing order on it. The ways that has been done have changed over time, but the imposition of order itself has been consistent. The order it produces, however fragile and conditional it might be, is very valuable, and we are deeply invested in it.

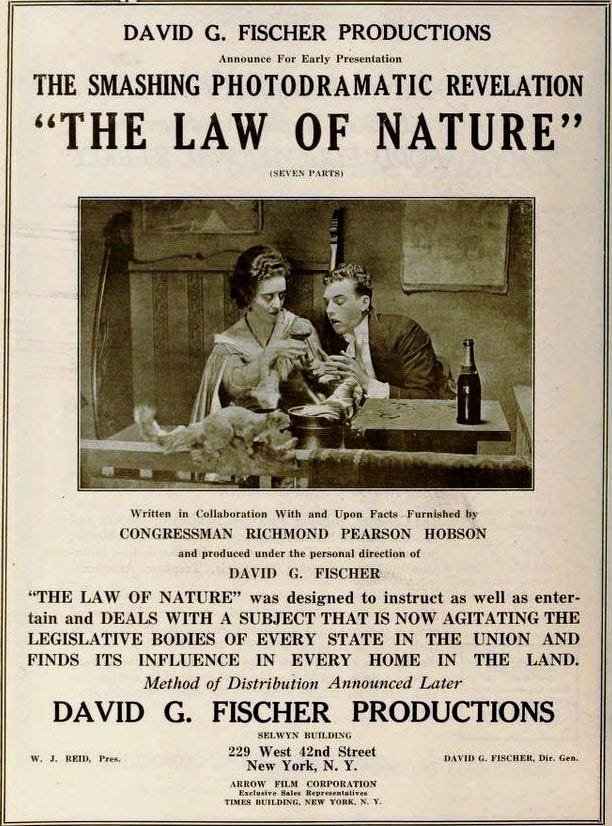

This is why human beings, writ large, tend to think about the sexual and gender rules of their cultures as having two essential qualities. First, they are spontaneous, things that “just are,” and second, they have origins from somewhere beyond human influence, instituted by a higher power of one sort or another. To bolster this idea, they’re often described with terms like “natural” or “organic” by those inclined to credit capital-N Nature, or “ordained” or “God-given” by those who view things through a supernatural lens.

Which source we invoke matters less than the outcome of framing the issue in this way. When we describe our sex and gender rules as originating from somewhere that humans don’t control, then we’re likely to understand them as being bigger than we are and quite literally unquestionable. This belief serves a function. Clear social boundaries protect order and reinforce social stability. The belief that those boundaries just happen to exist, are not and never were up to us, and can’t or shouldn’t be changed by human beings protects the boundaries themselves from challenges or changes.

When we approach doing research with presumptions about sexuality and gender that are both fully formed and well defended against investigation or criticism, it shapes what we look at, what we look for, and how we understand what we see.

Having these beliefs and biases makes it very difficult to objectively evaluate what actually exists, either behaviorally or biologically, in the routine goings-on of our species. This is especially true if we don’t perceive ourselves as having beliefs or biases, only an understanding of What Is True. Fish, as the saying goes, don’t notice the water they’re in. Why would they? Indeed, how could they?

This is the reason sex and gender research tends to be terrible: it’s very, very hard for us to get out of our own way. Noticing our own beliefs and biases is difficult and finding ways to look beyond them is even harder. As a result, most of the history of medicine and law, the two fields through which the largest amount of research on sexuality and gender has been carried out, have often approached these subjects from a standpoint that many analysts describe as “medico-moral” or “legal-moral.”

This means exactly what it sounds like it does: medical or legal understandings that are grounded in and shaped by ideas about morality and beliefs about what is right and correct.

Medico-moral thinking is the reason why, to pick a non-random example, we have plenty of research about questions like “what causes homosexuality?” (spoiler: we have no idea) and no research at all about the same question in regard to heterosexuality. Because homosexuality has been seen as the morally problematic exception, or the “crime against nature,” people have wanted to know why it exists. Heterosexuality’s not seen as a problem of any kind and certainly isn’t exceptional, so no one’s ever bothered to try to find out where it comes from.3 This is just one of the myriad ways that our moral beliefs shape our sexuality research.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Reasons Not to Quit to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.