This is the eighteenth and final installment in the series Get Your Facts Straight: Research Skills for Writers. For more about this 18-part series, including the complete schedule, click here.

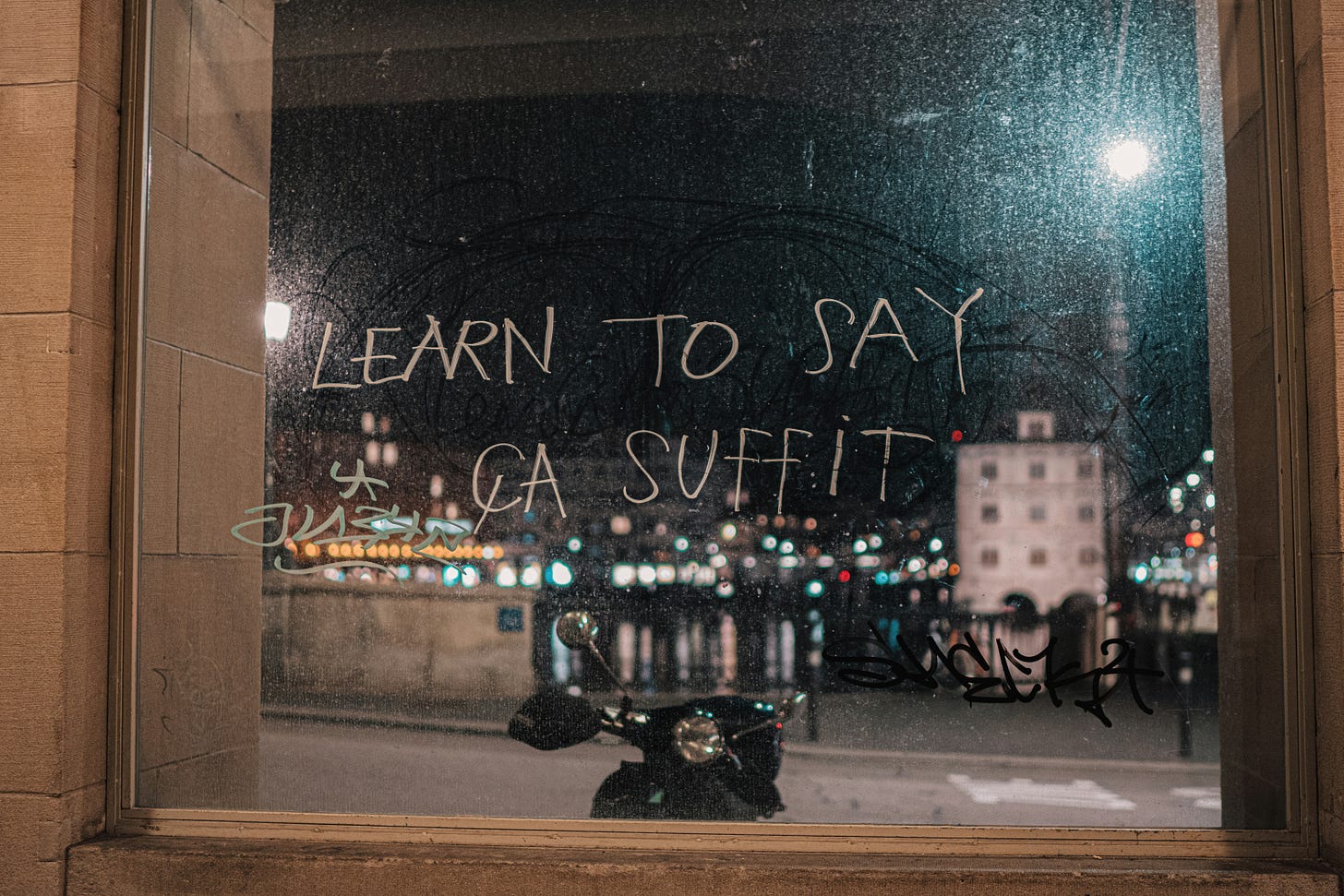

Say less.

There is no writing skill harder to master and no form of selectivity that is tougher for a researcher. Alas, it works. Brevity, as the saying goes, is the soul of wit. It also piques interest in ways length cannot.

As writing advice goes, “say less” seems counterintuitive. As a guideline for researchers, it seems almost insulting. Why on earth would someone go to all that trouble, spend all that time digging up all that information, in order to say less?

The answer is simpler than you might think. There are, in fact, two answers: engagement and curiosity. Both these things, of course, have to do with information. On a deeper and much more important level, though, they are emotions, things we feel.

Engagement is the emotion we feel when we are interested in something and our interest is being rewarded. It’s an enjoyable sensation, and one we will seek out, as the dopamine gumball machine that is the Internet has proven over and over again, whether or not we get anything more valuable than that moment of engagement out of doing so.

Information rarely engages the reader all by itself.

Information rarely engages the reader all by itself. This is another lesson well illustrated by the Internet: many things may engage us briefly, but fewer things sustain our interest. The success of the soundbite, the Tweet, and the image-based meme owe everything to the fickle flitting of our senses, attuned by millions of years of evolution to be sensitive to whatever new or different thing might make itself evident lest it represent a shining new opportunity (food! social interaction! sex!) or a scary new risk (predator! poisonous plant!) or something that could be either (fire!). The ability to instantly engage with something new has big potential rewards for an ambitious young organism-about-town.

But most of these moments of engagement require only the moment. Once we’ve assessed the new thing and discovered that it requires no action on our part, the engagement is over. We only stay engaged if we perceive a need for ongoing engagement. We only perceive the need for ongoing engagement if we want to interact with the thing further.

Do we want to eat it? Chase it? Run away from it? Do we want to admire it? Fondle it? Pick it up and carry it around for a while so we can show other people this cool thing we found? Or do we want something that has everything to do with the writers’ task: do we want to know more?

Curiosity is the emotion of wanting to know more. Most of the things that engage us — oh look! a squirrel! — don’t spur curiosity. What does spur curiosity? Mysteries do. Unexpected things do. Things that contradict our expectations often can. Things that spike an emotional response do it pretty reliably. Any time we become engaged and lack sufficient information to really complete our quick assessment of the new thing, we’re likely to feel at least a little bit of curiosity.

As you did, perhaps, when you saw the title of this essay in the context of an essay series on research skills for writers.

When a writer says less, the incompleteness of what they have said tends to engage the reader. In the first sentence of this essay, I took advantage of the fact that writing intended for adults rarely uses short declarative sentences to upset the expectation we know a reader is likely to bring to the page (or screen). If it got your attention, engaged you for a moment, then perhaps you paid enough attention long enough for curiosity to kick in. What does she mean, ‘say less’? About what? Why?

Exactly. For the writer, sparking curiosity is the whole point of creating that moment of engagement. Without some sort of curiosity, the reader won’t make it past the first paragraph, let alone turn the page.

Saying less is suggestive. It’s telegraphic. It hints at things. If the writer does it right, what isn’t said sparks the reader’s imagination: it engages their curiosity. When a reader’s curiosity is engaged, they continue reading.

Engagement and curiosity must be regularly, which is to say continuously, repiqued and rekindled throughout a piece of writing…

But this is not a one-and-done proposition. No writer can get away with engaging a reader just once at the start of a piece and expect the engagement to magically last no matter what comes after or how long or rambling it might be. Engagement and curiosity must be regularly, which is to say continuously, repiqued and rekindled throughout a piece of writing if the reader is going to follow you wherever it is you want to take them.

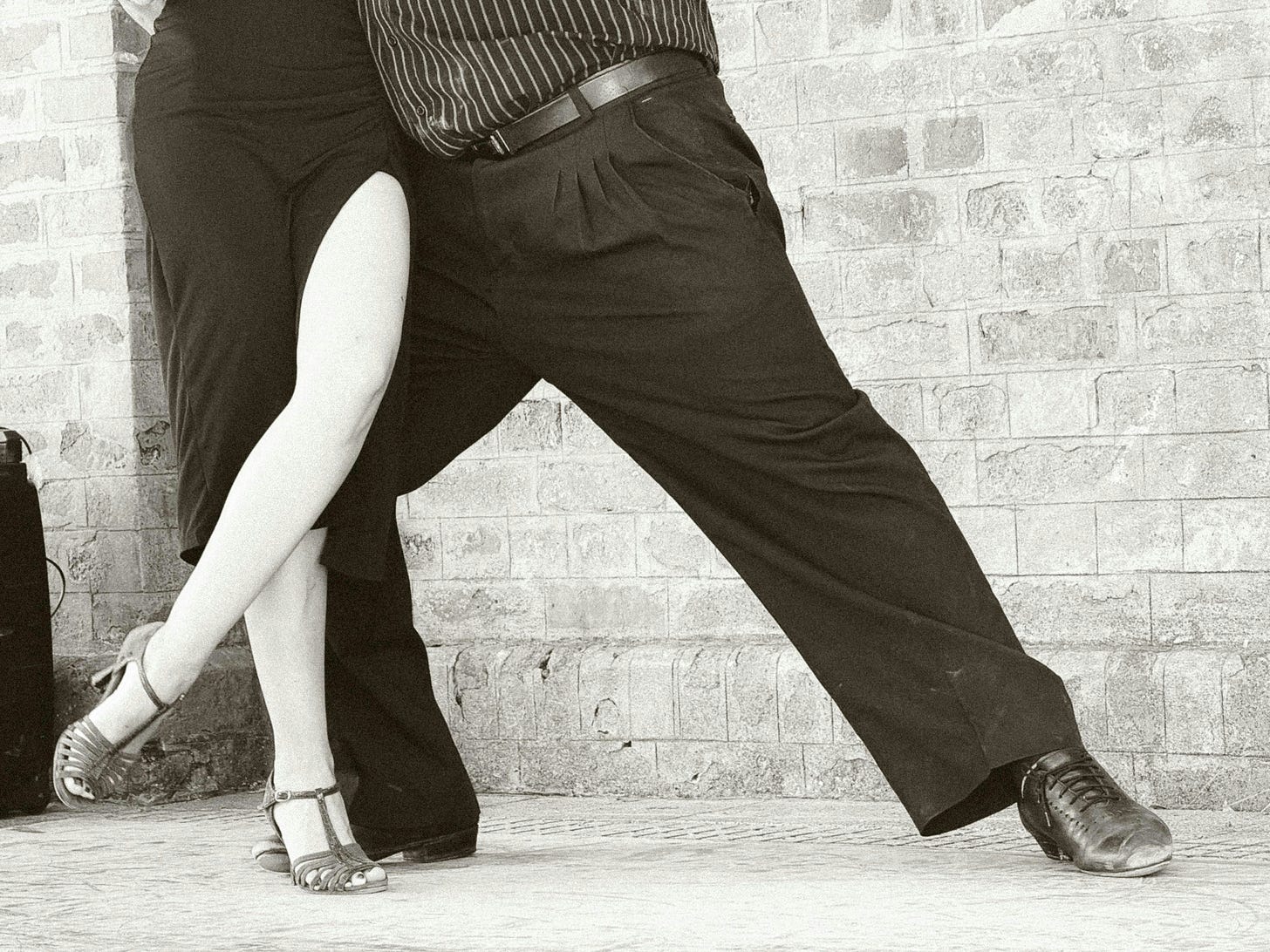

Doing this requires strategy in the form of information infrastructure, another name for having a strategy for what information you will give the reader when. The writer must think about the order in which the reader will be told things and how each bit of information performs part of the dance of engagement, curiosity, and fulfillment.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Reasons Not to Quit to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.