This is the twelfth installment in the series Get Your Facts Straight: Research Skills for Writers. For more about this 18-part series, including the complete schedule and the Table of Contents with links to all the other articles in the series, click here.

I’m not a doctor, or at least not the kind you want to talk to if you have appendicitis. I am, however, a medical historian, a bioethicist, someone who’s done clinical advocacy for over 20 years, and a person who’s done a considerable amount of writing about and within the field of medicine.

Medical research can be rough going for most people, including writers. As a field, medicine is characterized not just by specialization and an expectation of advanced training and education, but also by increasingly complex and sophisticated science and technology. Bodies themselves are also complicated and often not terrifically consistent, which can add considerably to the research burden when you’re trying to get and understand medical information because there are sometimes multiple reasonable answers to what might seem on the surface to be a simple, straightforward question.

The good thing is that as with researching almost anything else, there are tactics and strategies that can help you do better medical research and understand more about what you find. Going to medical school isn’t necessary, but learning to think a little more like a physician helps.

What do I mean by “thinking more like a physician”? Physicians are trained to think about medicine in terms of body systems, body parts and substances, typical ranges of variation, pathologies, injuries, diagnostics, therapies, mechanisms, and outcomes. Learning to think about medical questions in these terms helps you navigate research sources that have created with the assumption that these are the categories users will be thinking about.

Body systems — groups of organs and tissues that carry out a particular body function, for instance, the digestive system carries out nutrition and part of excretion

Body parts & substances — individual organs, tissues, structures, and substances produced by the body like eyes, blood, skin, liver, fingers, estrogen, saliva

Ranges of variation — the types of differences between human bodies and body functions that occur naturally, especially those that are statistically common

Pathology — any disease or disordered process of the body or one of its components; can be congenital (something someone is born with) or acquired (shows up after birth), can have single or multiple causes

Injuries — damage to the body or one of its components, can be caused by a disease or by trauma, for example, an abscess due to infection or a wound from a cut

Diagnostics — information used to determine the nature of a pathology or injury, also the process of making a diagnosis

Therapies — also known as treatments; any intervention intended to help or heal an injury, disease, or disorder, including things like drugs, surgeries, physiotherapy

Mechanisms — the processes and pathways of action that create changes in the body, whether harmful or helpful, for example, how bacteria cause infection or how aspirin reduces inflammation

Outcomes — the results of processes occurring in the body, whether related to diseases/disorders/injuries or therapies/treatments, for instance: the successful elimination of an infection through the use of an antibiotic is an outcome, but so is vision impairment due to uncontrolled diabetes

Thinking about medical research using these parameters helps you ask questions in ways that are more likely to be answered by medical sources. Almost all medical topics involve one or more body parts or substances and have some relationship to ranges of variation. “How many bones are in the human body?” and “How much do estrogen levels drop at menopause?” both deal exclusively with these two parameters.

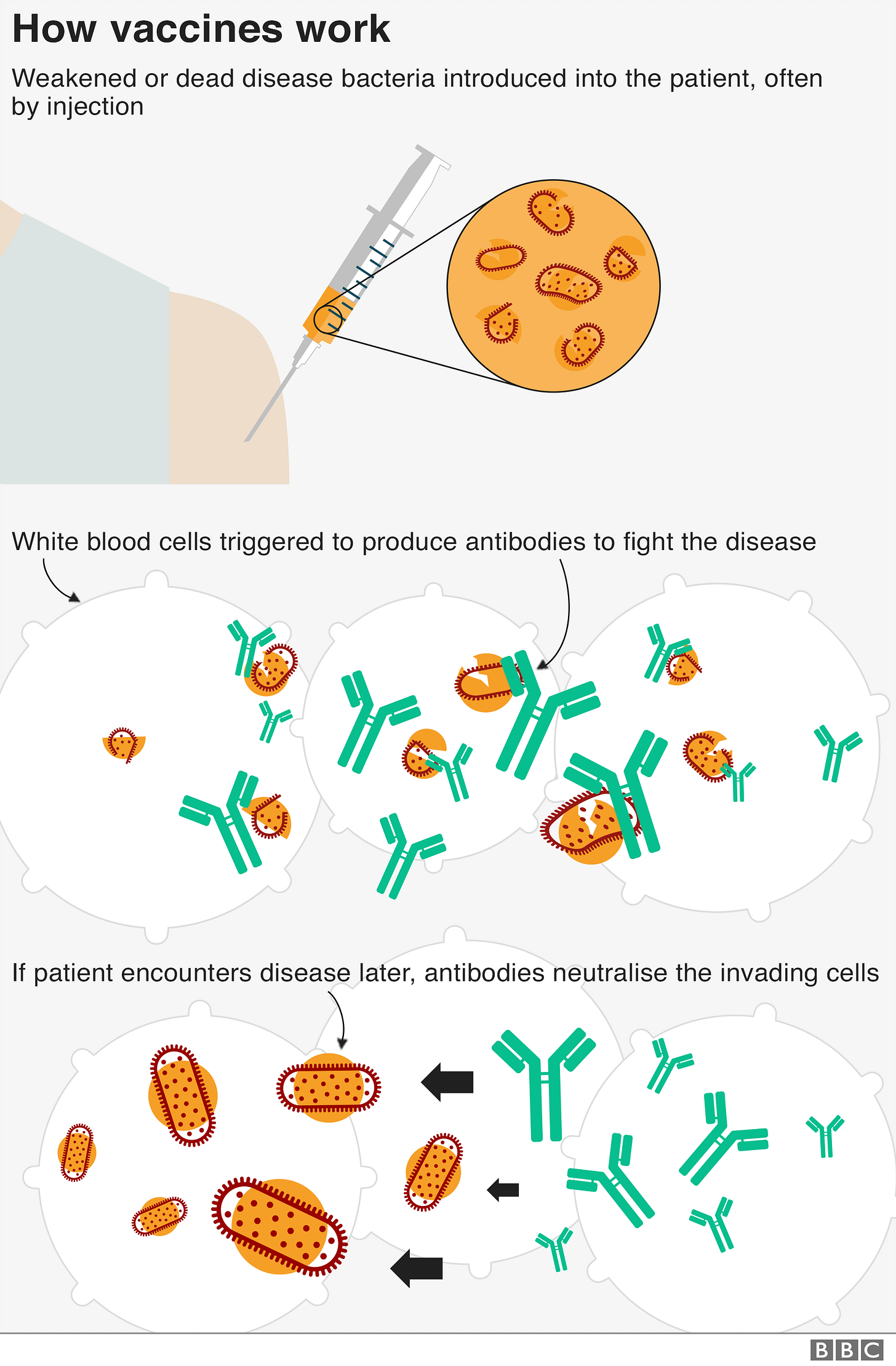

Many medical topics additionally involve pathology/injury plus mechanisms: “How does cancer harm people?” “If vaccines are made from disease-causing organisms (pathogens), why don’t vaccines make people sick?”

Others revolve around diagnostics: “How can you tell whether someone is at risk of stroke?” “What’s the difference between a Braxton-Hicks contraction and labor?”

Therapies are a common topic, and so are outcomes. These often go together, because the efficacy of therapies is measured by their outcomes. So “What is chemotherapy?” is a therapy question, while “Is surgery more effective at treating sciatica than physiotherapy?” is a question about therapies and outcomes.

Looking for these terms — pathology, injury, mechanism, outcome, treatment/therapy, diagnosis — as you do research helps you find the information you’re looking for. You can use them as signposts to identify particular kinds of information.

Figuring out what that information means is a separate step. You need experts, in the form of medical reference tools.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Reasons Not to Quit to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.