Following this post, Notes on Not Quitting will be taking a break for a bit to make space for some work that is going on behind the RNTQ scenes. The Reasons Not To Quit will continue to appear three times a week as usual, and you can be on the lookout for some newness on the horizon. (I’m excited, and think you will be too!)

If you’ve been considering supporting RNTQ with a paid subscription, may I encourage you to take the plunge? Writing is part of how I make my living, and that includes the writing I do here at RNTQ. It makes a real difference to me when readers choose to make an investment in my work. It is, in fact, what enables me to keep on doing it. Thanks.

One: Information about emotions is not always of high value.

I blame Freud. I know, cheap shot: he’s dead and an easy target. But also, let’s face it, there are plenty of things I could legitimately be blaming him for: he got a lot of things dreadfully wrong. One of them is the conceit that information about one’s inner landscape is always valuable. That’s the idea behind psychoanalysis, the notion that sifting one’s emotional sediment, analyzing and re-analyzing memories and traumas, somehow magically creates a cure for the myriad ways a person might feel wretched.

It is not that psychotherapy, even psychoanalysis, can’t be useful. It certainly can, especially in a world where it can be so difficult to find people who can be trusted to remain reflective but not reactionary when one dares speak the more difficult truths out loud. But processing one's emotions, on its own, may or may not get one where one needs to go.

It is tempting not only to feel but also to believe that experiencing and re-examining difficult, painful emotions must be valuable just because it is so damn taxing. I spent years convinced, in part because people repeatedly told me it was true, that doing heroic amounts of painful, exhausting emotional heavy lifting would inevitably solve things. It was a like-cures-like approach to emotional pain.

I now think that those people had it wrong. At best, they got it right insofar as exposure therapy can, like it says on the label, decrease one’s distress at being exposed to distressing things. This is sometimes unbelievably useful. (See also: that line often attributed to Viktor Frankl about stimulus and response and the space in between.)

Experiencing our emotions is inevitable, though the degree to which one is self-aware of their significance or willing to experience them deeply certainly varies. Self-awareness of your emotions is useful. It gives you information about how things affect you.

But any information is only as valuable as it is, and no more. Some things just aren’t that deep. If you’ve tried and failed to puzzle out the value or the meaning of a particular emotion or response, this might not be a failure on your part. It could just not have much. That’s how some things go.

Two: Pain can be meaningless.

I coexist with a little-understood type of brain or mind dysfunction that has been labeled “treatment-resistant depression.” When it kicks up, I feel emotional pain, sometimes murderously severe and constant emotional pain, for absolutely no reason at all.

This is precisely how I eventually lifted the lid off the trap of believing that an intense emotion of whatever sort must be providing valuable information just because it’s intense.

Feeling the emotional pain produced by a misbehaving brain is no more helpful than feeling the notorious agony of postherpetic neuralgia, which is to say it certainly lets you know something in the wiring isn't working right, whether or not there’s anything to be done for it. The pain of depression — or postherpetic neuralgia, for that matter — is not the same as the pain that tells you that you’ve touched the hot stove so you yank your hand away. It’s not the same as the pain that tells you that a wolverine has bitten your leg or that you have a UTI or that you’ve cut yourself slicing a bagel. (Pro tip: never slice toward your palm, it cuts just like any other meat.)

Some kinds of pain exist to yell at you about something actionable. Other kinds of pain just yell at you. It’s very helpful to be able to recognize which is which.

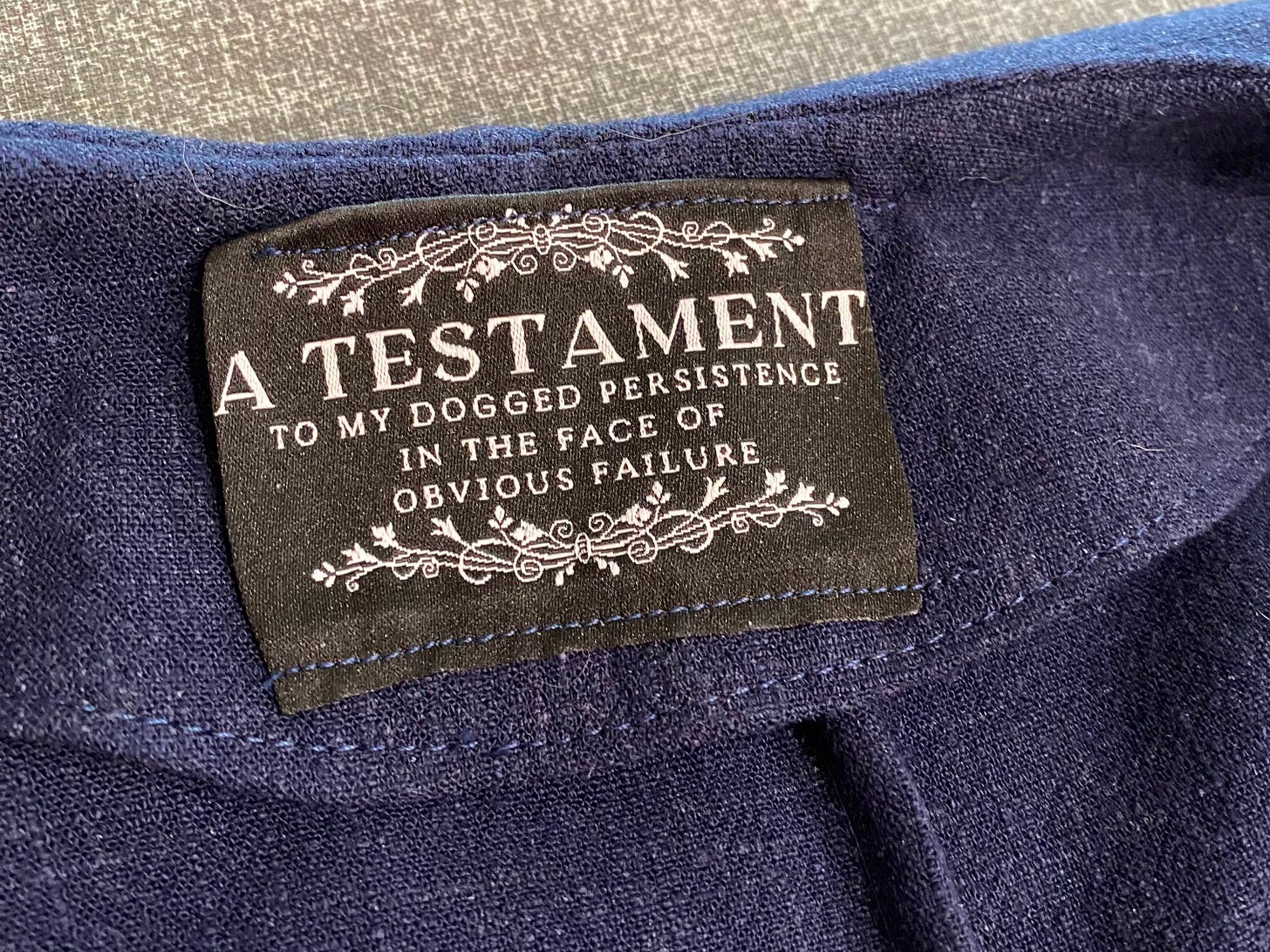

I can wrestle the brain-pain of depression for hours, weeks, and months, and I have. The only thing this has ever provided me is confirmation that it can be done.

I have also spent hours and weeks and years with therapists and psychiatrists trying to figure out what the unreasonable, intransigent, agonizing noise my brain was producing was trying to tell me. It turns out it was just yelling.

Brains, like other parts of our bodies, are capable of going haywire in stupidly horrible ways that are pure sound and fury, signifying nothing. It isn’t even evidence of cruelty. Cruelty requires intent. Biological accident is just entropy taking its cut. Meaning doesn’t always come along for the ride.

Three: No one is obligated to be grateful to something that harms them.

I have, from time to time, been exhorted to see the emotional agony of depression as a teacher. I’ve been told that I just have to (and I wish I were making this up) learn to express gratitude for its putative “gifts.”

I understand why people say these things. The impulse to demand reassurance makes sense: untreatable pain is horrible, and it could happen to you. But because lying about it is unhelpful and therefore unkind I won’t reassure you that pain is really just fabulous prizes in disguise.

Instead, I give you this: Welcome, friend, to this precious, precarious life. Some of the scenery is amazing and some of the company is superlative. The rest is a crapshoot, but try not to take your anxiety out on anyone. It doesn’t improve your odds anyhow. Come sit by me. It’s okay.

Four: Those who manage to transmute pain into better things deserve their flowers.

People who endure and survive a lot of pain do indeed learn things through the experience. Those things are often ugly. Hurt people hurt people, as the saying goes, because if being hurt teaches you anything, it's that being able to cause someone pain is a crude but effective path to power.

Sometimes, though, we manage to resist that temptation. Sometimes the experience of being hurt provokes us to refuse to use pain as a tool ourselves. We figure out how to do no harm. If we’re clever and also lucky we might even figure out how to be helpful instead, and maybe create joy and beauty.

We call doing this a triumph of the human spirit because that is what it is. Trust and believe that when someone learns how to do this it's they, and not the horrors they've been through, that deserve the credit.

Five: Breaking rocks is not the same as breaking out of prison.

Trust and believe, too, that suffering does not magically transmute into liberation from suffering. Suffering is a passive response. It is endurance and the submission endurance requires. Liberation, when it occurs, is the result of a deliberate and purposeful response to what has happened that includes audacious and insistent action.

Suffering can build certain kinds of strength. A prisoner forced to break rocks in the prison yard is, yes, breaking rocks. The effort is Herculean and it builds muscle. But the prison walls remain as sturdy as ever. Breaking rocks is not the same as breaking out of prison.

Suffering and action can coexist. They often must. This is not to say “shut up and suit up, the pain you’re in doesn’t matter.” That’s not true. The suffering does matter. But suffering won’t break you out of prison. Action might.

Proceed with the premise that the obstacle may be temporary.

Is this guaranteed to break you out of prison, whatever that prison might be? No. But building muscle only to use it to break more rocks in the prison yard is guaranteed not to. Creating a different future requires using those muscles differently. It also requires developing some different muscles.

That’s the work, and suffering, by itself, cannot do it.