Buttered

why butter in the US is not very good... and how it could be better

What does it mean to dream of butter?, I wondered, having just woken from one of those languid, indulgent late summer afternoon naps that leaves you feeling, for a passing moment anyway, comfortably close to post-orgasmic. The dream-mouthful of sables Breton I had been eating just an instant before was still so vivid that I could feel it crumbling between my teeth, and sense the bright sparkle of a crystal of salt against the mellow purr of butter and sugar.

I lay there for a few minutes, reluctant to break the spell, sense-memories of eating butter in various forms and formats careening through my thoughts: the yielding of a tangy salty chunk of butter thickly smeared on a hank of baguette bien cuit, the lush commingling of butter and honey melting on a plate of roast winter squash, the sweet-salt perfection of a spoon of warm foam skimmed from the pot of peach jam with a little curl of butter dropped in it, always one of the best treats of my childhood.

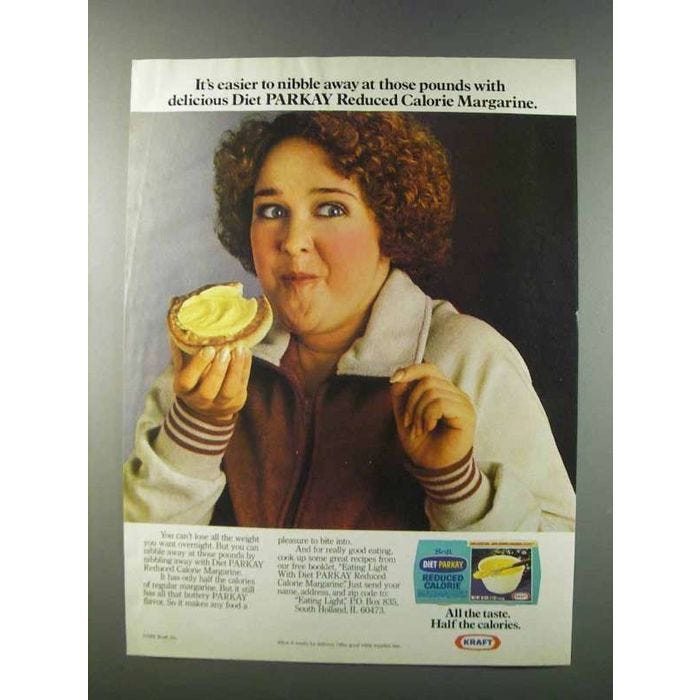

As I swung my legs over the side of the bed I flashed on my mother eating shingles of hard cold butter atop Saltines when she thought no one would know, shoving the sleeve of crackers irritably back into the box the instant someone wandered into the kitchen. In the U.S. of the 1970s and 1980s when I was growing up, many people including my mother saw butter as not just bad but Bad. It was fattening, which was certainly sin enough in her eyes. But it was also, simply, fat. Dietary fat was seen at the time as a nutritional nightmare, an edible epidemic, cause of heart attack and cancer and probably juvenile delinquency too. I grew up being earnestly told that butter was basically irredeemable, tantamount to piping cake frosting onto your baked potato. If one were going to insist on applying (say it with a sneer and a shudder) pure fat to your food, margarine made of unsaturated vegetable oils was the only acceptable option. Preferably a reduced-fat and reduced-calorie margarine at that.

Yet somehow there was always a stick or two of butter in the house. For my mother and so many like her eating butter was a deeply guilty pleasure, if “pleasure” is the right word at all for something that was nearly always furtive and shameful. When I walked in on her eating butter in thick pats that showed toothmarks when bitten through, her face flickered shame, then stony anger. It was clear that I would not be mentioning it again. Many years later she would be able to admit to loving this particular comfort dish, butter and jam on salty soda crackers. We even shared it once or twice, but never while I was a child. The only time I recall seeing her eat butter both openly and with actual pleasure was when we ate sweet corn on the cob in summer, when she lavishly buttered and salted each ear before she took a bite. What magic did an ear of sweet corn possess to make this possible? Simple. It had been a favorite treat of her childhood, ears picked from her parents’ backyard garden, shucked on the way to the kitchen door, and eaten hot at the kitchen table at a point in her life, and the nation’s, where both she and butter were still innocent and taking delight in good food was still an uncomplicated joy.

My mother’s love/hate relationship with butter has often struck me as symptomatic, maybe even emblematic, of the relationship that much of the US seems to have with the stuff. In the last couple of decades, foodie worship of the lush and the luxe as well as good old American decadence has wrested butter at least partially out of its 1970s-1980s infamy.

As a nation, though, we’re still pretty bad at butter. On the whole we don’t make or buy or eat good butter. And also on the whole we don’t seem to mind that our butter is so often shoddy stuff, partly because we still habitually echo the leper’s bells of a bygone orthorexia and partly because we tend to be ignorant of what good butter even is.

To be clear, profiteering is partially responsible. This is the USA, after all. One of European-descended white people’s calling cards around the colonized world is and has always been the system of totalizing economic fuckery we call capitalism.

(Should you still romantically cling to the idea that good upstanding godly Europeans came flocking to the Americas because they wanted freedom of worship, well, bless your well-indoctrinated little heart I guess, but no, no, and no. And should you not wish to believe scholars, take it from one of the many available horse’s mouths: Richard Hakluyt’s 1584 petition to Queen Elizabeth, asking her to sponsor colonization efforts in the Americas, is pretty dang clear about the economic and political motivations.)

I mention this because it should come as no surprise that butter, like pretty much everything else, has been subject to capitalism’s imperatives, and butter is not better for it.

Once upon a time, butter-making was a labor-intensive household or farm process that required a great deal of expertise as well as human and animal labor. Cattle had to be raised and fed and milked, milk had to be allowed to settle so the cream would rise, cream had to be separated off the milk, and only then could that cream be churned into butter, kneaded, washed, salted to extend its useful life, and packed into containers for storage. How much butter could be produced at any given time was limited by the quantities of cream human beings or animals (for instance, using a dog-powered butter churn ) could physically churn at one time.

To give you some idea of what that meant, contemporary hand-crank butter churns tend to hold from a liter to three liters of cream, although you can find small-industry crank-powered models that will hold 12 (a little more than 3 gallons). Plunger churns or barrel churns usually max out around 11 liters (around 3 gallons). Bearing in mind that cream yields somewhere between 35-50% butter by volume, and that butter becomes gradually more difficult to churn as the butterfat solidifies, a little back-of-the-butter-wrapper math suffices to enlighten us that this works out to a fairly large amount of labor for a not-all-that-large quantity of butter: a gallon (3.8 L) of milk to about 1/3 to 1/2 pound (151-226 g) of butter is a rough metric.

No wonder dairymaids were known for their hardworking ways. Milkmaiding was a sought-after and economically valuable trade, one of very few that was historically primarily practiced by women. That they had heroically buff upper bodies (note the substantial shoulders and visible forearm muscles on Vermeer’s famous milkmaid below) and were often immune to smallpox was a bonus.

But times have changed, and most of us get our butter with no more effort than it takes to put it in our shopping carts. Butter has become a commodity, and a cheap one too, requiring very little investment for the consumer. Economies of scale and the vast size of the US and its markets have played their roles in this, and so have technologies like pasteurization, industrial mechanization, mass transportation, and, of course, refrigeration. Now, motorized industrial butter churns can handle several thousand liters (500 gallons or more) of cream at one time. Industrial mixers whose bowls could easily serve as hot tubs are used to mix in salt and in many cases also air: air decreases density which makes butter spread more easily when it’s cold. American butter companies often make whipped butters that incorporate a great deal of air for exactly this purpose; some also make butters that have added vegetable oil for the same reason. (As far as I can tell this is a strictly American phenomenon, born of a reluctance to leave butter out on the kitchen counter in a butter dish, which in my experience the rest of the butter-eating world does without a second thought.)

Financially speaking there’s a lot to be gained by doing it the new-fashioned way. That’s why it’s done. But never forget: in a capitalist system, “efficiency” means fewer people who must be paid, and paying those people you cannot do without as little as possible in order to maximize the amount of profit that streams directly to the business owners.

What gets sacrificed in the process is not a mystery. You might’ve noticed, for instance, that dairymaids have gone extinct. As for the farmers and the cows that still have to exist if we’re to have butter at all, their lives and livelihoods genuinely suffer as a result of the economic pressures of big agriculture.

The quality of the food we end up being able to purchase suffers too. Cows that aren’t able to thrive don’t give great milk. Milk that isn’t good doesn’t produce good cream. What cows are fed affects the flavors in their milk and cream, too, and the flavors inherent in their feed show up in whatever comes out of the udder, which becomes a bigger issue the more dairy cows are fed on things other than forage.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Reasons Not to Quit to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.